By 2030, one in five people in the U.S. will be over 65. That’s 71 million seniors needing help with daily tasks - bathing, dressing, eating, medication management. And right now, there aren’t enough workers to meet that demand. The care economy isn’t just growing; it’s collapsing under pressure. Health and elder care jobs are among the fastest-growing in the country, but wages are low, hours are brutal, and turnover is sky-high. This isn’t a future problem. It’s happening right now in nursing homes, home care agencies, and hospitals across the country.

What Exactly Is the Care Economy?

The care economy includes every job that involves directly supporting people’s daily physical, emotional, and medical needs. That’s home health aides, nursing assistants, personal care workers, dementia specialists, hospice nurses, and even the cleaners and cooks in long-term care facilities. These aren’t glamorous roles, but they’re essential. Without them, seniors can’t live with dignity. And increasingly, they can’t live at all.

Unlike tech or manufacturing, the care economy can’t be automated. You can’t build a robot that holds a dying person’s hand or recognizes when an elderly patient is confused and needs reassurance. These jobs require human presence, patience, and emotional labor - skills that machines still can’t replicate.

Why Are These Jobs So Hard to Fill?

Let’s be honest: most people don’t want to work in elder care - and for good reason.

Wages are abysmal. The median hourly wage for a home health aide is $14.20. That’s less than minimum wage in many states after you account for travel time, fuel, and out-of-pocket expenses. A certified nursing assistant in New Mexico earns about $15 an hour. Meanwhile, a warehouse worker in the same town pulling boxes off shelves makes $19. The work is physically demanding - lifting, bending, standing for 12-hour shifts - and emotionally draining. You’re caring for people who forget your name, who yell, who resist help. You’re often the only person they see all day.

Benefits are scarce. Less than half of home care workers have health insurance through their employer. Paid sick leave? Rare. Retirement plans? Almost nonexistent. Turnover rates in home care hover around 60% annually. In nursing homes, it’s even worse - some facilities lose 100% of their staff each year.

And then there’s the stigma. Care work is still seen as "women’s work" - low-skill, low-value. It’s not viewed as a career. It’s viewed as a last resort. That mindset has to change.

Where Are the Workers Coming From?

Right now, the care workforce is mostly made up of immigrant women, especially from Latin America, the Philippines, and Eastern Europe. In Albuquerque, nearly 70% of home health aides are Latina. Many are undocumented or on visas, making them vulnerable to exploitation. They work long hours for little pay because they have few other options.

But this isn’t sustainable. Immigration policies are tightening. Many of these workers are aging themselves. And their children aren’t always eager to follow in their footsteps. The pipeline is drying up.

Meanwhile, younger Americans are choosing other paths. Nursing school is expensive. The training is grueling. And the payoff? A paycheck that doesn’t match the stress. Why spend years becoming a registered nurse if you’re going to be overworked and underpaid?

What’s Being Done - And What’s Not Working

States are trying. New Mexico raised the minimum wage for home care workers to $15.25 in 2024. California passed a law requiring nursing homes to maintain minimum staffing ratios. The federal government added $2 billion in Medicaid funding for home and community-based services in 2023.

But these are Band-Aids.

Wage increases don’t fix the lack of benefits. More funding doesn’t fix the fact that most agencies still operate on razor-thin margins. Staffing ratios sound great - until you realize there aren’t enough trained people to fill those roles.

Training programs exist, but they’re underfunded. Community colleges offer certification courses for nursing assistants, but few students finish because they can’t afford to quit their other jobs. Childcare is a huge barrier. Many care workers are single mothers. Without affordable daycare, they can’t attend class - let alone take the exam.

And employers? Most are still treating care work like a temporary gig. They hire, train for a week, and expect workers to handle complex medical needs on day two. No mentorship. No career path. Just burnout.

Real Solutions That Are Already Working

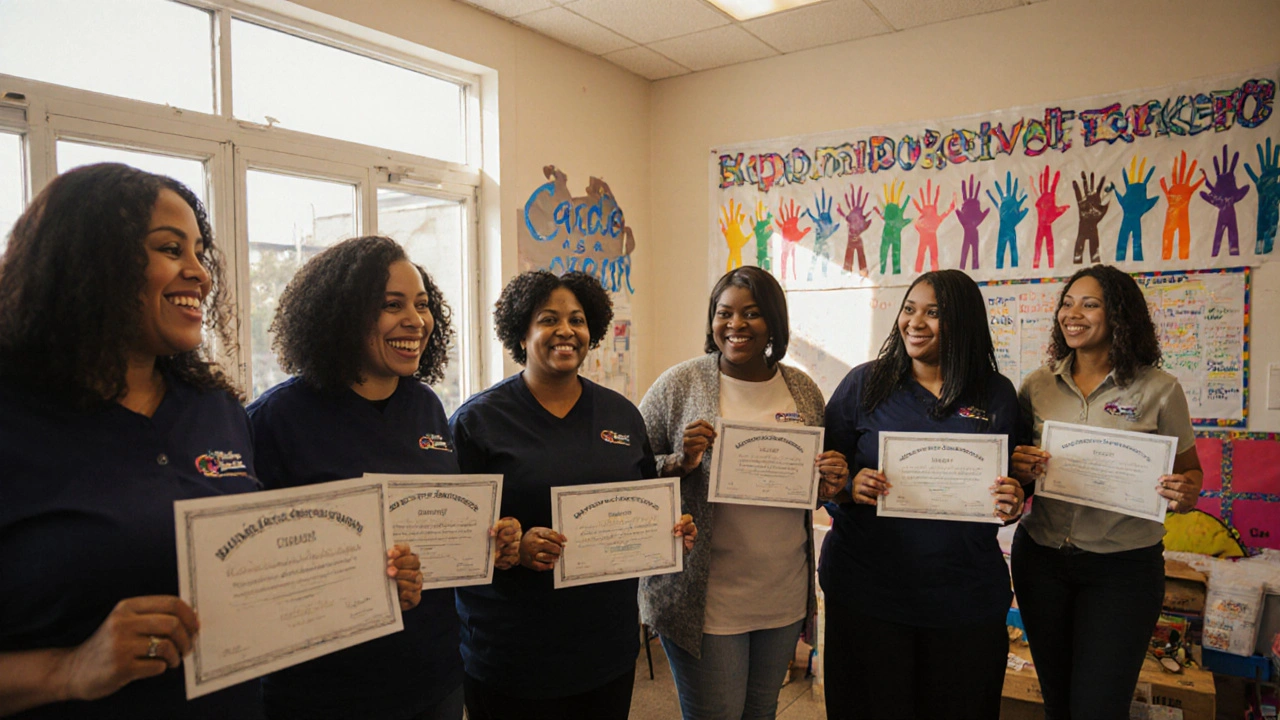

There are places where change is happening - and it’s not because of federal mandates. It’s because local leaders did something radical: they treated care work like a real profession.

In Portland, Oregon, a nonprofit called CareForce created a career ladder. A home health aide can earn a certificate in dementia care, then move into a supervisor role, then into case management - with pay increases at each step. They offer tuition reimbursement for nursing school. They provide free childcare during training. And they guarantee a job at the end.

Results? 82% of participants stayed in the field after two years. That’s unheard of.

In Minnesota, a coalition of home care agencies started paying a living wage - $22 an hour - and offering paid time off, health insurance, and retirement contributions. They raised prices for clients by just 5%. Most families agreed. Why? Because they saw the difference. Their loved ones weren’t being neglected. Staff weren’t quitting every month.

These aren’t charity cases. They’re business models that work.

What Families and Policymakers Can Do

If you have an aging parent, you know the struggle. You’ve called agencies. You’ve waited months for an aide. You’ve watched your parent decline because no one was there to help.

Here’s what you can do:

- Ask providers: "Do your workers get health insurance? Paid leave? Are they paid above minimum wage?" If they say no, look elsewhere. Demand better.

- Support local ballot measures that fund home care services. In 2024, voters in Colorado approved a $100 million annual fund for care workers. It passed by 22 points.

- Advocate for Medicaid expansion. Most care workers are paid through Medicaid. If your state hasn’t expanded it, push for it. It’s the single biggest source of funding for this workforce.

At the policy level, we need three things:

- Universal benefits for care workers - health insurance, paid sick days, retirement plans - no matter where they work.

- Public investment in training - free or low-cost certification programs with childcare and stipends.

- Recognition - treat care work like nursing or teaching. Give it professional status. Celebrate the people who do it.

The Future Isn’t Optional

We are heading toward a future where millions of Americans will need daily help to live. And we’re not ready. We’ve built a system that depends on exploited labor - mostly women of color - and called it sustainable.

The truth is, we can’t afford not to fix this. The cost of inaction is higher than the cost of investment. More hospitalizations. More ER visits. More families burned out. More seniors dying alone.

Fixing the care economy isn’t about charity. It’s about survival. We need to pay care workers enough to live. We need to train them properly. We need to respect them as professionals.

Because one day, that aide who helps your mother bathe? That’s going to be you.

Why are care workers paid so little despite high demand?

Care work is historically undervalued because it’s been seen as "women’s work" and tied to charity or family duty, not professional labor. Most funding comes from Medicaid, which pays low rates, and agencies cut costs by keeping wages down. There’s no strong union presence in home care, and many workers are immigrants with limited bargaining power. The system was built to be cheap, not sustainable.

Can technology replace care workers in the future?

No - not for the core tasks. Robots can remind someone to take medicine or call for help, but they can’t hold a hand, recognize emotional distress, or adapt to unpredictable behavior. Dementia patients often reject machines. Human connection is the most effective treatment for loneliness and depression in older adults. Technology can assist, but it can’t replace the human presence.

What’s the difference between a home health aide and a nursing assistant?

A home health aide typically helps with daily living tasks - bathing, dressing, meal prep - and may have basic medical training. A certified nursing assistant (CNA) works in facilities like nursing homes and is trained to take vital signs, assist with medical equipment, and report changes in condition. CNAs need state certification; home health aides may not, depending on the state. Both are essential, but CNAs have more clinical responsibilities.

How can I become a care worker without going into debt?

Many community colleges offer free or low-cost CNA programs, especially if you qualify for workforce development grants. Some states, like Washington and Oregon, pay for training if you commit to working in the field for a year. Nonprofits like CareForce and local Area Agencies on Aging often provide stipends and childcare during training. You don’t need a four-year degree - just a 6- to 12-week course and a state exam.

Is elder care a good career path for young people?

Yes - if the system improves. The job market is booming: the Bureau of Labor Statistics projects 1.3 million new care worker jobs by 2032. With proper pay, benefits, and advancement paths, this can be a stable, meaningful career. Many workers move from aide to CNA to LPN to RN. It’s not just a job - it’s a calling with real upward mobility, if the system supports it.

Next Steps for Employers and Communities

If you run a home care agency, start here: pay $20 an hour. Offer health insurance. Let workers take a day off when they need it. Train them properly. You’ll spend more upfront - but you’ll save money on recruitment, overtime, and liability from turnover.

If you’re a city council member, fund a care worker corps. Partner with local colleges. Offer childcare vouchers. Create a public recognition program. Celebrate care workers like you do firefighters or teachers.

If you’re a family member - speak up. Don’t accept substandard care. Ask for better. Demand transparency. Your voice matters more than you think.

The care economy isn’t broken because we don’t have enough workers. It’s broken because we don’t value them enough. Fix that, and everything else follows.