Commercial Space Revenue Calculator

About This Tool

This calculator helps you estimate potential revenue and risk for commercial space missions based on payload type, mission duration, and business model. Based on real data from the article about Axiom, Vast, and Starlab.

Estimated Revenue

Estimated Costs

Profit Margin

By 2025, space isn’t just for governments anymore. It’s a marketplace. Companies are building stations, launching satellites, and selling access to microgravity - all while navigating complex rules, tight budgets, and technical risks. The old model - NASA building everything, flying everything, paying for everything - is over. What’s replacing it is messy, exciting, and full of uncertainty. If you’re trying to understand how science gets into orbit, who’s making money, and who’s actually in charge, here’s what’s really happening.

Science Payloads: What’s Actually Flying Today

Science on commercial missions isn’t just about waving a flag in zero-G. It’s about specific tools, precise environments, and hard data. The payloads flying now are wildly different depending on who’s paying and what they need.Axiom Space’s modules on the ISS carry an 80-centimeter Earth observation window. That’s not for tourism. It’s for monitoring climate patterns, crop health, and urban growth with higher resolution than most satellites. Researchers from universities and environmental agencies book time on it - they get data, Axiom gets revenue.

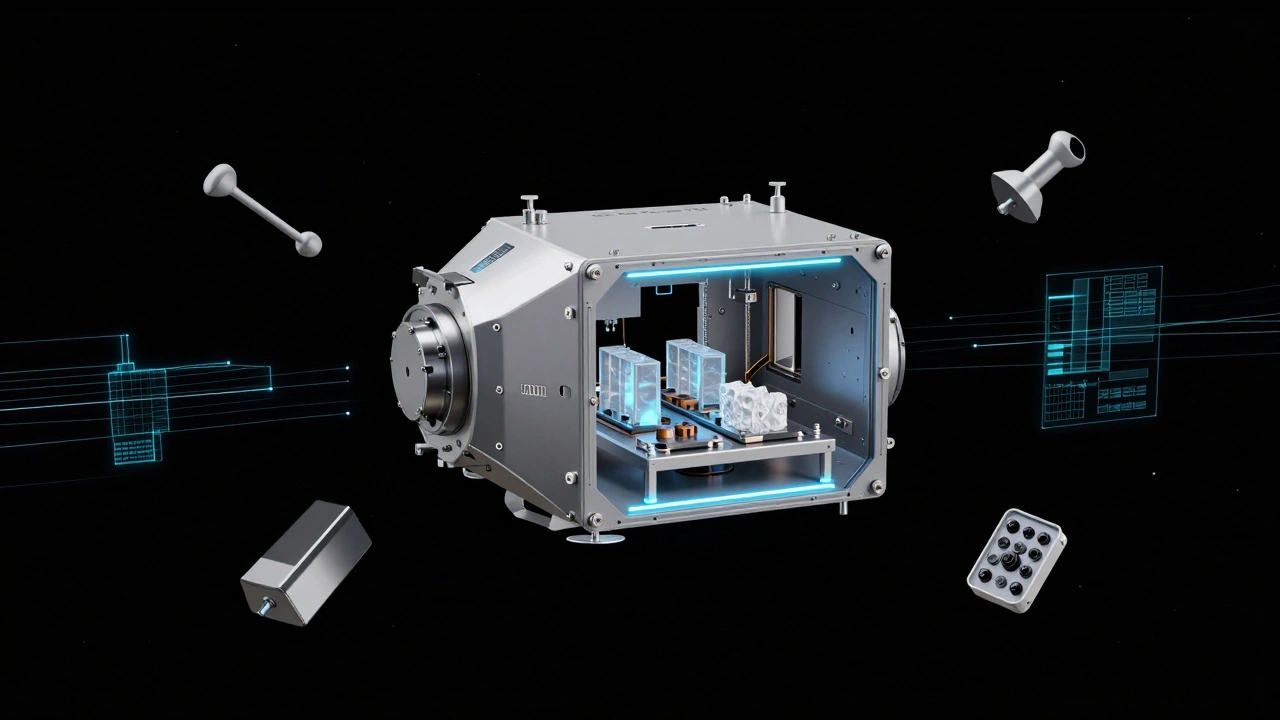

Vast’s Haven-1, launching in August 2025, carries a 500-kilogram Microgravity Research Platform. That’s a dedicated rack for materials science experiments - think growing perfect protein crystals for drug development or testing new alloys that won’t melt under stress. It’s small, focused, and designed for short missions of up to 60 days. No fancy life support, no long-term habitation. Just science, fast and cheap.

Starlab, set to launch in 2028, is different. Its 340-cubic-meter inflatable module is built for long-duration experiments. That means biological studies - how human cells behave over months, how plants grow in partial gravity, how fluids move without convection. Pharmaceutical companies are already lining up. One leaked internal document from a major drug maker shows they’ve reserved 18 months of time for protein crystallization trials.

But here’s the catch: not everything works. Firefly Aerospace’s Blue Ghost lunar lander delivered 10 science payloads to the Moon in March 2025. Nine returned data. One failed completely because of thermal swings. That’s 10% of the science lost before it even started. Vibration during launch, temperature spikes in orbit, bandwidth limits - these aren’t theoretical problems. They’re daily headaches for payload teams. NASA’s own Q1 2025 anomaly report says 37% of commercial payloads have issues linked to launch stress. Fixing them adds $250,000 to $500,000 per experiment. That’s not a line item. It’s a dealbreaker for many university labs.

Revenue Models: Who Pays, and Why

There’s no single way to make money in commercial space. Each company has a different playbook.Axiom Space uses a hybrid model. NASA paid $140 million to attach its first modules to the ISS. That’s public money covering infrastructure. Then they charge private astronauts $55 million per seat on missions like Ax-4. That’s luxury tourism. On top of that, they’re pricing future station leases at $1.8 million per day. That’s not for fun. That’s for companies running experiments that need continuous microgravity - think semiconductor manufacturing or bioprinting tissues. Their revenue isn’t one stream. It’s three overlapping ones.

Vast is betting on direct sales. Haven-1 isn’t meant to be a hotel. It’s a lab. They’re targeting research institutions with a flat fee of $12 million per mission. That includes launch, docking, power, data downlink, and mission control. No frills. No crew. Just science. They’re also selling media rights - think live streams of experiments from orbit - to science networks and educational platforms. Their whole model is about volume: run 10 missions a year, make $120 million. Simple. Aggressive. Risky.

Starlab’s approach is government-heavy. CEO Tim Kopra said in April 2025 they’ve secured letters of intent worth $1.2 billion from seven national space agencies. That’s not a guess. That’s signed paperwork. Seventy percent of their projected revenue comes from government contracts - NASA, ESA, JAXA, and others. The other 30%? Pharma. Companies like Merck and Novartis are paying to run long-term cell studies. Starlab’s size and duration make it ideal for this. But if those government deals fall through? Their whole business model collapses.

Orbital Reef? That’s the entertainment play. Blue Origin’s internal documents from February 2025 show they’re projecting $500 million a year from media rights and experiential tourism. Think: live concerts from orbit, branded VR experiences, celebrity missions. It’s not science. It’s spectacle. And it’s expensive to produce. But if they can turn space into a TV show, the margins could be huge.

The market is splitting into three tracks: government-funded science, private research labs, and pure entertainment. Most companies are trying to straddle two or three. But only a few will survive.

Regulatory Paths: The Hidden Cost of Getting to Orbit

You can build the perfect satellite. You can design the safest capsule. But if you don’t get the paperwork right, you never leave the ground.The FAA’s Office of Commercial Space Transportation licensed 1,000 space operations by August 2025. Sounds impressive, right? But the average time to get a launch license? Nine to twelve months. If your rocket uses new propulsion tech? Add another three to six months. That’s not a delay. That’s a bottleneck. Maria Garcia, an FAA regulatory specialist, testified in April 2025 that most delays come from reviewing novel engine designs - not safety failures. Just unfamiliar tech.

Spectrum allocation is another silent killer. Small satellite operators report that 78% face delays because they’re waiting for international approval to use radio frequencies. The ITU - the United Nations body that manages space radio bands - moves slower than most governments. A startup might spend $2 million on a satellite, then wait 18 months to get permission to talk to it.

And then there’s debris. The FCC is still debating new rules for how long satellites can stay in orbit after they die. Right now, companies can leave dead satellites up for 25 years. That’s not enough. But changing the rule means retrofitting existing designs - or scrapping them. One company, AstroForge, told me their 2026 mission is on hold because they can’t decide whether to add extra fuel for deorbit or risk non-compliance. That’s the regulatory trap: you’re forced to guess what rules will exist next year.

For science teams, the regulatory burden is worse. Integrating a payload takes 18 months on average. Universities need another six to nine months of help just to understand the paperwork. Corporate teams have lawyers. Academic teams have grad students. The gap is widening.

Who’s Winning - and Who’s Falling Behind

Space isn’t a race. It’s a survival contest.Axiom has the advantage of timing. They’re already on the ISS. Their modules are flying. Their first private astronaut mission sold out in hours. They’ve proven they can deliver. But their station is tied to the ISS. When the ISS deorbits in 2030, they’ll have to launch their own free-flying station - and they haven’t built it yet. Their timeline is tight.

Vast is moving fastest. Haven-1 launches in August 2025. It’s the first free-flying commercial station. But it’s small. Only 300 cubic meters. Can’t hold more than four people. Needs constant reboosts from other spacecraft. It’s not a long-term solution. It’s a proof of concept. And if it fails? Vast’s entire brand is built on speed.

Starlab has the biggest vision - and the biggest risk. Their inflatable module is 70% larger than the ISS’s Harmony module. But MIT’s Space Structures Lab found their prototype has 37% less resistance to micrometeoroid impacts. That’s not a small flaw. That’s a potential catastrophe. If a tiny piece of space junk punches through, the whole station depressurizes. They’re betting on materials science. If they’re wrong, they’re out.

Orbital Reef looks impressive on paper - 1,000 cubic meters of space, rigid and inflatable parts, tourism-ready. But their biggest customer? Tourists. And tourists are fickle. Virgin Galactic’s customers gave them a 68% satisfaction rating - but 89% said it wasn’t worth $450,000. If people stop paying to float for four minutes, Orbital Reef’s revenue model vanishes.

SpaceX isn’t building stations. But they control the launch market. They did 217 of 301 commercial launches in 2025. That’s 72% of the market. If SpaceX raises prices or delays Starship refueling - which is now pushed to 2026 - every other company feels it. Their rockets are the pipeline. If the pipeline dries up, the whole industry stalls.

The Real Risk: The Gap Between ISS and the Future

The biggest threat isn’t technology. It’s timing.NASA plans to retire the ISS in 2030. But none of the commercial stations are guaranteed to be ready by then. Starlab’s first launch is 2028. Axiom’s independent station? Not until 2030. Vast’s Haven-1? Too small to replace ISS science. That leaves a two- to three-year gap.

Former NASA Deputy Administrator Lori Garver warned in May 2025 that this gap could mean the U.S. loses leadership in low Earth orbit. China’s Tiangong station is already operational. They’re not waiting. They’re running experiments. They’re training astronauts. If American science goes dark for three years while China keeps working, the momentum shifts.

NASA’s own budget request for 2026 includes only $150 million for commercial station development. The National Academies said they need $250 million. That’s a $100 million hole. That’s not a funding shortfall. That’s a strategic risk. If the government pulls back too soon, the private sector can’t fill it. The market isn’t mature enough yet.

And here’s the kicker: NASA says commercial stations will save $1 billion a year by replacing the ISS. But that’s only true if they’re running at full capacity. If only one station is operational, and it’s half-empty? Those savings vanish. The math only works if multiple stations succeed - and they all get customers.

What Comes Next

By mid-2026, NASA will pick one or more commercial stations to certify as official replacements for the ISS. That decision will decide who survives. If Starlab gets the nod, inflatable tech becomes the standard. If Axiom wins, modular expansion is the future. If Orbital Reef is chosen? Tourism becomes space policy.For science teams: Start talking to companies now. Don’t wait for NASA to announce a new program. Reach out to Axiom, Vast, Starlab. Ask what payloads they’re accepting. What bandwidth do they offer? What thermal limits do they have? What’s their response time if your experiment fails? These aren’t abstract questions. They’re the difference between data and disaster.

For investors: Look beyond the hype. Don’t bet on the flashiest station. Bet on the one with the clearest revenue path and the strongest partnerships. Axiom has NASA and private customers. Vast has speed and focus. Starlab has scale - if their structure holds.

For regulators: The FAA and FCC need to move faster. Licensing can’t take a year. Spectrum can’t be a bureaucratic maze. The industry is ready. The rules aren’t.

Space is no longer a frontier. It’s a business. And like any business, it rewards those who understand the real costs - not just the launch price, but the time, the risk, the paperwork, and the waiting. The next decade won’t be about who gets to space. It’ll be about who stays.

What are the main science payloads flying on commercial space missions in 2025?

In 2025, key payloads include Axiom Space’s 80-centimeter Earth observation window for climate and agriculture monitoring, Vast’s 500-kilogram Microgravity Research Platform for materials science, and Starlab’s large inflatable module designed for long-term biological and pharmaceutical experiments. Firefly Aerospace’s lunar landers also carried payloads for lunar surface science, though several experienced thermal failures. Payloads are increasingly specialized - focused on data collection, not just demonstration.

How do companies like Axiom and Vast make money from space missions?

Axiom Space uses a hybrid model: NASA funds their ISS modules, they charge $55 million per private astronaut seat, and plan to lease station time at $1.8 million per day for commercial research. Vast sells direct access to its Haven-1 station for $12 million per mission to research institutions and supplements income with media rights. Starlab relies on government contracts (70% of revenue) and pharmaceutical research, while Orbital Reef targets tourism and entertainment revenue through media and branded experiences.

Why is regulatory approval such a big hurdle for commercial space companies?

Regulatory approval takes 9-12 months on average, and newer propulsion systems can add another 3-6 months. Spectrum allocation for communications requires international coordination through the ITU, causing delays for 78% of small satellite operators. Debris mitigation rules are still being debated, forcing companies to design around uncertain future standards. These delays cost time and money, often derailing mission schedules before launch.

What’s the biggest risk to the future of commercial space stations?

The biggest risk is a gap between the ISS retirement in 2030 and the readiness of commercial stations. If no station is certified and operational by then, U.S. science loses access to low Earth orbit for years. China’s Tiangong station is already active, and without continuity, American leadership in space research could decline. Funding shortfalls - NASA’s 2026 budget request is $100 million below what experts recommend - make this gap more likely.

Which commercial station design is most likely to succeed long-term?

Axiom has the strongest near-term position due to existing ISS integration and proven revenue streams. Starlab has the largest capacity and strongest government backing, but its inflatable design faces unproven risks in micrometeoroid protection. Vast moves fastest but lacks scale. Long-term success depends less on design and more on revenue stability. Axiom’s mix of public and private funding gives it the most resilience. Starlab could win if its structure proves safe and its government contracts materialize. Others risk collapse without consistent demand.