By 2025, hyperscale data centers are no longer just big server rooms-they’re city-sized power hogs, water-intensive cooling plants, and strategic geopolitical assets. If you think cloud computing is just about software and apps, you’re missing the physical reality: every video stream, AI model, and online purchase runs on a machine that needs 10 megawatts of electricity, 2 million gallons of water a year, and a location that won’t shut it down because the grid can’t keep up.

Power Constraints Are the New Bottleneck

Amazon, Google, and Microsoft are building data centers faster than utilities can upgrade the grid. In 2024, Google requested 1.2 gigawatts of new power in Nevada alone-enough to power 900,000 homes. That’s not an outlier. In Iowa, Microsoft’s data center expansion pushed local utilities to pause new connections for over a year. The problem isn’t just supply-it’s timing. Data centers need power now, but grid upgrades take five to seven years.

Most hyperscale facilities pull power directly from the transmission grid, not local distribution lines. That means they bypass the usual bottlenecks… until they don’t. In 2023, a substation failure in Northern Virginia knocked out three major cloud providers for six hours. The root cause? Too many high-demand data centers feeding into the same transformer. Utilities are now forcing companies to sign multi-year power purchase agreements (PPAs) just to get on the waiting list.

Some operators are turning to on-site generation. Apple’s data center in Maiden, North Carolina, runs on a 100% renewable microgrid with solar panels and fuel cells. Meta’s facility in Sweden uses excess heat from servers to warm nearby homes. But these are exceptions. The rule? Power constraints are slowing down cloud growth faster than any software limitation ever could.

Cooling Innovation: From Water to Liquid and Back

One server rack generates as much heat as a space heater. Now imagine 10,000 racks in a single room. Traditional air cooling-think giant fans and chilled air ducts-isn’t just inefficient; it’s unsustainable. A single hyperscale data center can use up to 2.5 billion gallons of water a year just for cooling. In drought-prone regions like Texas and Arizona, that’s a dealbreaker.

Enter liquid cooling. Companies like NVIDIA and Google are shifting to direct-to-chip cooling, where coolant flows through metal plates attached to each processor. This cuts energy use by 30-40% and reduces water consumption by over 90%. Intel’s latest Xeon processors are designed specifically for immersion cooling, where servers sit in non-conductive fluid. It sounds like sci-fi, but it’s already live in Microsoft’s Finnish data center.

But liquid cooling isn’t a magic fix. It’s expensive. Installing it in an existing facility can cost $15 million more than retrofitting air cooling. That’s why most operators are hybridizing: air cooling for lower-density areas, liquid for AI and GPU clusters. The trend? Liquid cooling will be standard in new hyperscale builds by 2027-not because it’s cheaper, but because water permits are getting harder to get.

Siting Decisions: Where You Build Matters More Than What You Build

Choosing where to build a data center isn’t about cheap land anymore. It’s about access to power, water, climate, and political stability. The old rule-build near cities for low-latency access-is dead. Today’s top locations are remote, cold, and grid-strong.

Sweden’s data center corridor near Stockholm is packed because of its stable hydropower, 10°C average temperatures, and strong environmental laws that favor efficiency. Finland’s data center hub in Hamina uses seawater for cooling and gets 90% of its electricity from nuclear and wind. Even in the U.S., Oregon’s The Dalles is a hotspot-not because it’s near Portland, but because it sits on the Bonneville Power Administration grid, one of the cleanest and most reliable in the country.

On the flip side, regions like Texas and California are seeing a cooling-off period. Texas has the land and low taxes, but its grid is fragile. California has the talent and demand, but water restrictions and wildfire risks make large-scale builds risky. Companies are now using AI-driven siting tools that score locations on 20+ variables: grid stability scores, historical outage rates, water availability projections, and even local political support for tech infrastructure.

The winners? Places with excess renewable energy and cold climates. The losers? Urban areas that can’t upgrade their infrastructure fast enough. In 2025, the most valuable real estate isn’t in Silicon Valley-it’s in rural Iceland, where geothermal power runs at 100% capacity and the air is naturally cold enough to cool servers without chillers.

The Hidden Cost: Workforce and Supply Chain Risks

Building a hyperscale data center isn’t just about buying servers. It’s about finding engineers who know how to install liquid cooling systems, electricians certified for high-voltage DC systems, and supply chains that can deliver specialized components on time.

The global shortage of qualified data center technicians is worsening. In the U.S., there are only 12,000 certified data center engineers-half the number needed to support current growth. Companies are partnering with community colleges to create 12-week bootcamps in data center operations. Meta and Google now hire veterans and military technicians-they already know how to manage complex systems under pressure.

Supply chain risks are equally real. In 2023, a fire at a Taiwanese chip plant delayed cooling pump deliveries for six months. A single component failure can halt an entire build. That’s why top operators now require dual sourcing for critical parts: two suppliers for chillers, three for power distribution units. They’re also keeping six months of spare parts on-site-something unheard of five years ago.

What’s Next? The Next Generation of Data Centers

The future isn’t just bigger data centers-it’s smarter ones. Modular designs are replacing traditional brick-and-mortar builds. Facebook’s Open Compute Project has made open-source server designs standard, cutting costs by 30%. AI now predicts cooling needs in real time, adjusting fan speeds and pump flows before temperatures spike.

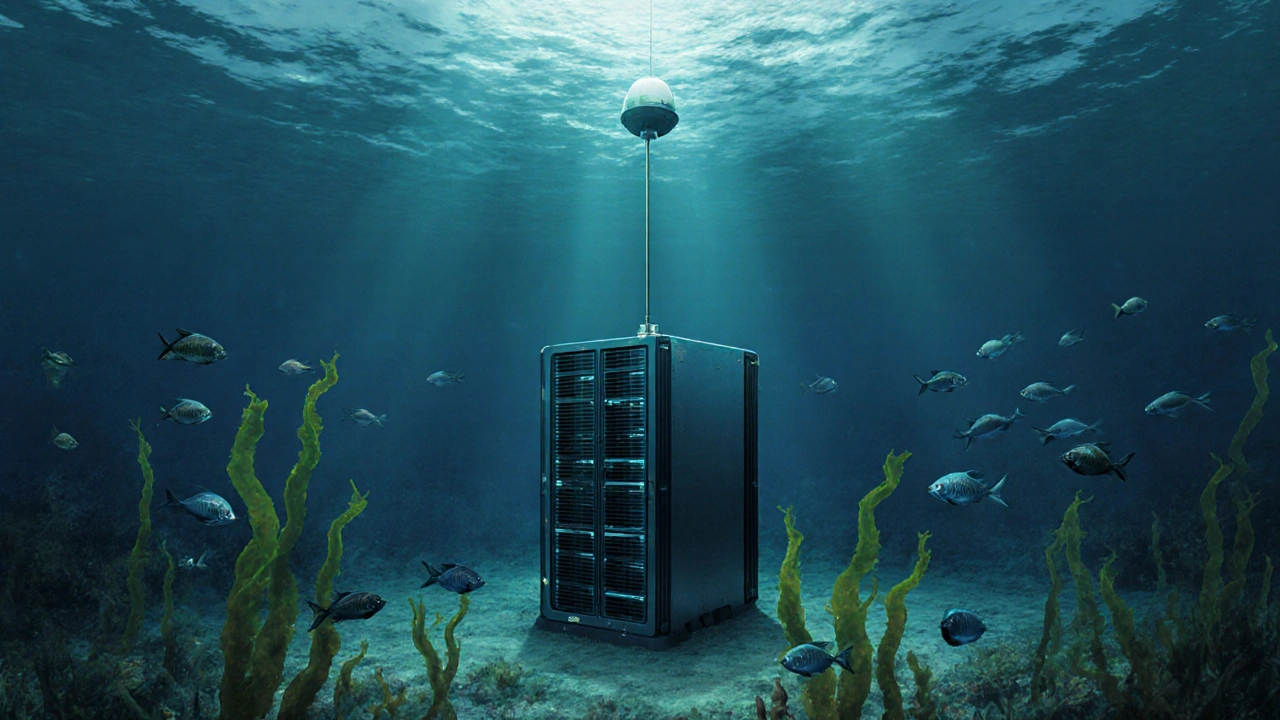

Some are even experimenting with underwater data centers. Microsoft’s Project Natick buried a container of servers off the coast of Scotland. It ran for two years with zero maintenance, cooled by the ocean, and used zero freshwater. It wasn’t cheaper-but it proved that location can be engineered, not just chosen.

One thing is clear: the next wave of cloud innovation won’t come from faster processors or better algorithms. It’ll come from how we handle power, water, and place. The companies that master these physical constraints will own the next decade of digital infrastructure. The rest will be stuck waiting for the grid to catch up.

Why can’t hyperscale data centers just use more solar panels?

Solar panels alone can’t meet the continuous, 24/7 power demand of a hyperscale data center. A typical 100-megawatt facility needs over 300 acres of solar panels to generate its annual energy-most of which would need to be stored in batteries, which aren’t yet cost-effective at that scale. Solar is used as a supplement, not a primary source. Most operators rely on grid power backed by long-term renewable energy contracts.

Are liquid cooling systems more reliable than air cooling?

Yes, in high-density environments. Liquid cooling removes heat more efficiently and reduces the risk of hot spots that cause hardware failure. Air cooling relies on airflow, which can be disrupted by dust, cable clutter, or uneven rack placement. Liquid systems are sealed and less prone to environmental interference. However, they’re more complex to install and maintain, so they’re best suited for AI and GPU-heavy workloads-not general-purpose servers.

Why are data centers moving to rural areas instead of cities?

Cities lack the power capacity and water access needed for hyperscale builds. Grid congestion, zoning laws, and public opposition make urban expansion nearly impossible. Rural areas offer access to underutilized transmission lines, lower land costs, and colder climates that reduce cooling needs. Latency isn’t a major issue for cloud services-most users connect via fiber networks that span thousands of miles without noticeable delay.

How do data centers get water permits today?

Water permits are now the biggest hurdle in the U.S. and Australia. Regulators require proof of water sustainability, reuse plans, and alternative cooling methods. Many facilities must demonstrate they’ll use less than 1.2 gallons of water per kilowatt-hour of power consumed. In California, new data centers must submit a 20-year water plan. Some operators are now using recycled wastewater or desalinated water to meet these standards.

Is there a limit to how big a data center can get?

Yes-there’s a physical limit tied to power delivery and heat dissipation. A single building can’t exceed about 150 megawatts without risking grid instability or overheating. That’s why operators now build clusters of smaller facilities instead of one giant campus. Google’s data center in Council Bluffs, Iowa, is made up of 12 separate buildings, each under 100 megawatts, connected by underground power and cooling conduits. Size isn’t the goal anymore; resilience is.