PEF Trigger Calculator

Pandemic Emergency Financing Facility (PEF) Triggers

Enter data from early pandemic stages to see if it would have triggered PEF payouts. Note: The PEF required 12 consecutive weeks of sustained conditions.

Results

Note: The PEF required 12 consecutive weeks of these conditions before payout could occur. This calculator shows single-week thresholds only.

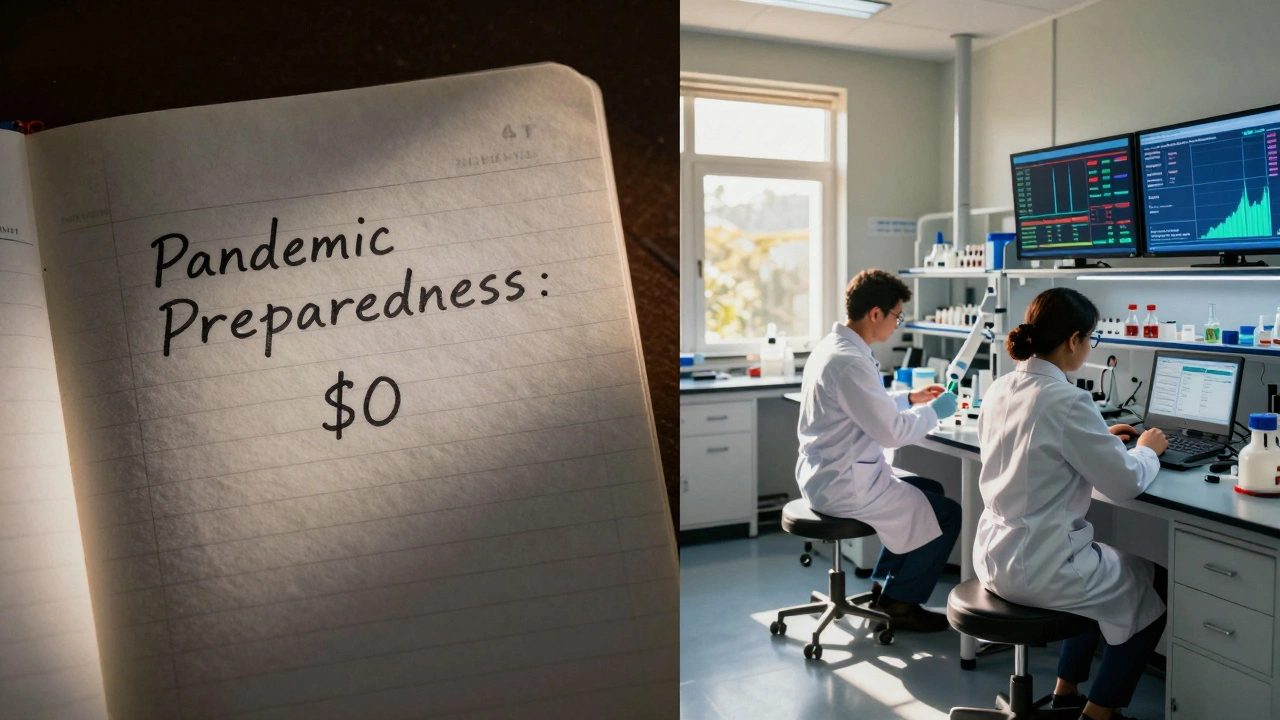

When the first cases of COVID-19 started appearing in early 2020, countries scrambled for money. Hospitals needed masks. Labs needed tests. Governments needed cash-fast. But one of the world’s most advanced financial tools for exactly this kind of crisis sat silent. The Pandemic Emergency Financing Facility (PEF), a $425 million insurance mechanism built by the World Bank, was designed to pay out the moment a pandemic began. Instead, it waited. And waited. And by the time it paid out, the world was already in chaos.

How the PEF Was Supposed to Work

The PEF wasn’t a charity. It wasn’t even a traditional aid program. It was a financial product-specifically, a set of catastrophe bonds sold to private investors. Think of it like hurricane insurance, but for viruses. Investors bought bonds that paid high interest-up to 11.1% above U.S. LIBOR-if nothing happened. But if a pandemic hit, those bonds would pay out to governments in need. The structure was complex. There were two classes of bonds. Class A, worth $275 million, paid out if a disease met three criteria: at least 750 cases, 250 deaths, and a 10% weekly case growth in two or more low-income countries. Class B, worth $150 million, had higher thresholds: 2,500 cases, 500 deaths, and 20% weekly growth in three countries. And here’s the kicker: these conditions had to be met for 12 straight weeks before a payout could even be considered. The pathogens covered? Influenza, Ebola, coronaviruses, and a few rare hemorrhagic fevers. For coronaviruses, the maximum payout was $195.83 million-but only if the outbreak met the Class B threshold. Investors were told this was a smart way to shift risk from poor countries to Wall Street. The World Bank called it innovation. Critics called it a trap.Why It Failed in Practice

By March 2020, the WHO declared COVID-19 a global pandemic. The world was shutting down. But the PEF didn’t pay out. Why? Because the trigger conditions weren’t met. Here’s the problem: in the early days of an outbreak, case numbers are low. Testing is limited. Deaths are still climbing. The PEF needed 12 weeks of sustained growth-by then, the virus was already spreading in over 100 countries. In Senegal, public health officials were begging for funds to buy oxygen concentrators. In Nepal, hospitals had no ventilators. But the World Bank’s payout committee, working with an independent verifier in London, spent weeks checking data. The system was designed to avoid false alarms. But in a fast-moving crisis, avoiding false alarms meant letting real ones kill people. The first payout-$195.83 million-didn’t come until April 2020. By then, over 1.5 million cases had been reported worldwide. The money arrived too late to help contain the outbreak. It arrived to help with recovery, not response. Epidemiologists were furious. Dr. Ashish Jha of Brown University called it “financial goofiness.” The Center for Global Development said the PEF was built for a pandemic that looked like the 1918 flu-not the kind we actually face today, where speed matters more than scale. Reddit users in public health forums joked that the PEF was “waiting for people to die before it acted.”The Human Cost of Delayed Funding

The PEF wasn’t just slow-it was structurally unfair. Low-income countries with weak surveillance systems couldn’t even meet the data requirements. If a country didn’t have enough labs to count cases accurately, it couldn’t trigger the payout. So the system punished the very people it was meant to protect. Dr. Amina Jallow, who led disease control in Senegal, told the Global Health Security Agenda Network: “We needed funds immediately when cases first appeared, not months later when the outbreak had already overwhelmed our systems.” Her country had only 12 confirmed cases when the first wave hit. The PEF required 2,500. That’s not a policy failure. That’s a moral failure. Meanwhile, investors in Class B bonds made out like bandits. Because the payout didn’t happen quickly-or fully-they kept collecting interest. The 11.1% premium was a sweet deal. But the people who paid for that premium-the poorest nations-got nothing when they needed it most.

What Replaced the PEF

By December 2020, the World Bank admitted the PEF didn’t work. It announced it wouldn’t renew the program. The bonds expired in July 2020. The $195.83 million payout was the only one ever made-and it came too late to matter. In its place, the World Bank launched the Pandemic Fund in 2022. This time, no parametric triggers. No 12-week waiting periods. No complex formulas. Just grants. Up to $1.7 billion in flexible funding, available when countries ask for it. No verification delays. No investor protections built into the design. Just money, fast. The shift was clear: public health can’t be outsourced to hedge funds. You can’t price human lives based on case growth rates. The new fund doesn’t rely on financial engineering. It relies on trust-and speed.What’s Next for Pandemic Financing?

The PEF’s failure didn’t kill the idea of private-sector involvement in pandemic risk. It just killed the idea that complex financial triggers are the right tool for public health. Today, experts are pushing for hybrid models. Imagine a fund that combines:- A small, fast-disbursing grant window for early response

- A separate insurance layer that kicks in only after a certain threshold (say, 10,000 deaths globally), to cover long-term recovery

- Real-time data sharing from WHO and national labs to reduce verification time to days, not weeks

The Bigger Lesson

The PEF was a product of a world that believes finance can solve everything. But health crises aren’t market failures. They’re human failures. You can’t insure against panic. You can’t hedge against grief. You can’t securitize a mother’s fear when her child can’t breathe. The real innovation wasn’t the bond structure. It was the realization that when a pandemic hits, the fastest way to save lives isn’t to wait for a trigger. It’s to have money ready-no strings attached. The PEF taught us that complexity is the enemy of speed. And in a pandemic, speed is the only thing that saves lives.What Countries Should Do Now

If you’re a government official in a low- or middle-income country, here’s what you need to do:- Don’t rely on future pandemic bonds. They’re not coming back.

- Build your own emergency cash reserve-even if it’s just $5 million. Keep it liquid.

- Join the World Bank’s Pandemic Fund. Apply for grants before a crisis hits.

- Work with WHO to improve your disease surveillance. Better data = faster funding.

- Push for regional pooled funds. Ten countries together can negotiate better terms than one alone.