Vaccine Manufacturing Hub Estimator

Based on article data: Technology transfer timelines vary from 18-36 months. Infrastructure costs range from $50M-$500M. Africa currently produces less than 1% of global vaccines while Latin America produces 25% and Southeast Asia 35%.

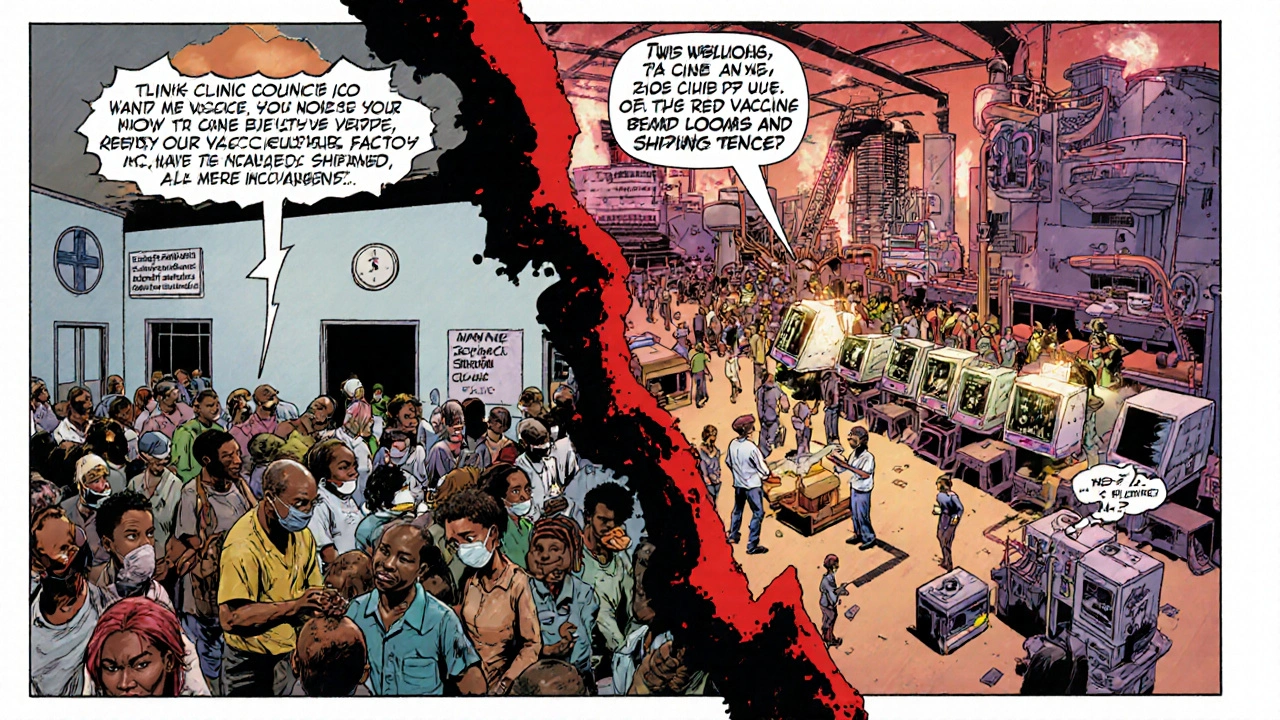

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, the world watched as rich nations snapped up the first doses of vaccines-leaving poorer countries behind. By mid-2022, 85% of Africa’s population had not received a single dose. Meanwhile, the Serum Institute of India, the world’s largest vaccine producer, shipped over 1.8 billion doses globally. The problem wasn’t lack of supply. It was lack of access. And the root cause? A system built on centralized manufacturing, where a handful of companies in Europe, North America, and India controlled nearly all production. That system failed the world when it needed to work the most.

Why Regional Hubs Are No Longer Optional

The old model of vaccine production relied on a few giant factories, often thousands of miles from where the vaccines were needed. When outbreaks happened, shipping delays, export bans, and political bargaining meant people waited months-sometimes over a year-for life-saving shots. In 2021, 11 billion doses were made globally, yet most never reached low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). The reason? Supply chains were designed for profit, not equity. Regional manufacturing hubs change that. Instead of waiting for vaccines to arrive from overseas, countries can produce them locally. The Pasteur Network, a coalition of vaccine producers across nine African and Latin American countries, already produces over 525 million doses a year. These aren’t pilot projects. They’re operational factories with trained staff, GMP-certified facilities, and real-world experience. In Africa, five manufacturers are set to produce eight WHO-prequalified vaccines by 2030. Five more commercial-scale plants are waiting for technology transfer. This isn’t future talk-it’s happening now.How Technology Transfer Actually Works

You can’t just hand over a recipe and expect someone to make a vaccine. Technology transfer is a multi-year process that includes training, equipment, quality control systems, and regulatory support. For viral vector vaccines like AstraZeneca’s, it takes 18-24 months. For mRNA vaccines-like Pfizer and Moderna’s-it can take two to three years because the science is more complex and the supply chain for raw materials is fragile. The International Vaccine Institute (IVI) has trained over 2,000 professionals from LMICs since 2022 through its Global Training Hub in Korea. These aren’t entry-level workers. They’re engineers, quality control specialists, and regulatory experts who return home to build and run their own facilities. One key insight from IVI: 78% of LMIC manufacturing sites struggle to find people with advanced bioprocessing skills. That’s why training isn’t an add-on-it’s the foundation. Technology transfer also means sharing not just know-how, but intellectual property. Dr. Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, Director-General of the WTO, made it clear: equitable access requires freedom to operate without patent barriers. Some pharmaceutical companies still resist, but pressure is mounting. The WHO’s Emergency Use Listing (EUL) process has been streamlined since 2020, and as of November 2025, 12 African-made vaccines have received WHO prequalification-up from just 3 in 2020.The Infrastructure Behind the Hubs

Building a vaccine manufacturing hub isn’t like opening a small clinic. It’s a massive, capital-intensive project. A single facility needs at least 10,000-15,000 square meters of space, clean rooms, cold storage, and fully automated filling lines. GMP certification alone costs between $50 million and $100 million. A medium-scale plant capable of producing 100 million doses annually can cost $200-500 million to set up. That’s why financing is critical. The African Union’s Partnership for African Vaccine Manufacturing (PAVM) secured $1.2 billion in June 2024 to fund production over the next decade. That’s not just a donation-it’s a long-term investment with clear targets: 60% local vaccine production in Africa by 2040. The European Union, Gates Foundation, and Gavi have also pledged billions, but funding gaps remain. Gavi’s 2026-2030 strategy aims for $11.9 billion; as of June 2025, only $9 billion had been pledged. Another hidden cost? Regulatory systems. Africa has 55 countries and 47 different regulatory agencies. Compare that to the European Medicines Agency, which covers 30 countries with one unified system. Harmonizing standards across regions is one of the top priorities for the Regionalized Vaccine Manufacturing Collaborative (RVMC). Without it, a vaccine approved in Nigeria might still be blocked in Kenya.

Who’s Leading the Way-and Who’s Falling Behind

India is the standout success story. In 2010, the Serum Institute of India produced 50 million doses a year. By 2024, it was making 1.8 billion. That growth didn’t happen by accident. It was driven by government policy, targeted subsidies, and long-term industrial planning. Today, Indian manufacturers supply 60% of UNICEF’s vaccine needs. That’s the model other regions are trying to copy. Southeast Asia is next, with 35% of its vaccines now produced locally. Latin America sits at 25%. Africa? Less than 1%. That gap isn’t about talent or will-it’s about investment, infrastructure, and political commitment. The Pasteur Network’s model is promising because it doesn’t try to build isolated national factories. Instead, it connects existing facilities across nine countries to share resources, training, and supply chains. It’s a network, not a collection of silos. The U.S. and EU still dominate high-value vaccines like shingles, HPV, and RSV. But in lower-cost vaccines-polio, measles, tetanus-manufacturers in India, Indonesia, and China now control the market. That’s where regional hubs can compete. They don’t need to beat Pfizer. They just need to make enough doses, affordably, for their own populations.The Real Barriers: Money, Time, and Politics

There are three big obstacles standing in the way of equitable vaccine manufacturing:- Cost and timeline-It takes 3-5 years to go from planning to production. Most donors want quick wins, not decade-long investments.

- Regulatory fragmentation-Without harmonized standards, a vaccine made in Senegal might not be accepted in Ghana. That’s a dealbreaker for regional distribution.

- Predictable demand-No factory can survive if it’s only used during emergencies. The African Union’s plan to buy 15% of its vaccines from local manufacturers by 2030 is the first real signal that demand will be consistent.

What Success Looks Like by 2030

By 2030, we should see:- At least 15-20% of global vaccine production coming from regional hubs, up from less than 5% today.

- Five to seven new WHO-prequalified vaccine manufacturers in Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia.

- Regulatory harmonization covering at least 20 countries across two or more regions.

- Local manufacturers producing vaccines for diseases that affect their own populations-Ebola, Marburg, mpox, TB-not just ones that are profitable for Western companies.

What Comes Next?

The next five years are critical. Funding must be locked in. Regulatory bodies must align. Workforce training must scale. And governments must commit to buying locally-not just when there’s a crisis, but every year. The technology is ready. The people are trained. The models exist. What’s missing is the sustained political will. If we wait until the next outbreak to act, we’ll be right back where we started-with millions waiting, and the same few companies holding all the power.Why can’t we just produce more vaccines in high-income countries?

High-income countries already produce most of the world’s vaccines-but they prioritize their own populations first. During the pandemic, countries like the U.S. and the U.K. bought up over 78% of initial doses. Even if production increased, the system still favors wealthy buyers. Regional hubs ensure that vaccines are made where they’re needed, reducing delays and dependency.

How long does it take to build a vaccine manufacturing hub?

From planning to full production, it takes 3 to 5 years. The technology transfer process alone takes 18-36 months, depending on the vaccine type. mRNA platforms require longer validation because of complex storage and handling requirements. Infrastructure, workforce training, and regulatory approval add additional time.

Are regional vaccine hubs more expensive than importing?

Initially, yes. Per-dose costs can be 20-30% higher during the first few years because of setup costs and lack of economies of scale. But over time, as production ramps up and supply chains stabilize, costs drop. More importantly, the cost of *not* having local production-delayed responses, higher mortality, economic disruption-is far greater.

What role does the WHO play in vaccine manufacturing equity?

The WHO sets global standards for vaccine safety and quality, including prequalification, which is required for UN procurement. It also runs training programs, supports technology transfer through its Biomanufacturing Training Initiative, and helps harmonize regulatory systems. In 2025, it released a report specifically calling for catalytic financing to help LMIC manufacturers scale up.

Can regional hubs produce mRNA vaccines like Pfizer and Moderna?

Yes, but it’s harder. mRNA vaccines require specialized equipment, ultra-cold storage, and highly trained staff. A few African and Latin American facilities are now producing them through technology transfer deals. The Pasteur Network and South Africa’s Biovac Institute have both started pilot mRNA production. Full-scale capacity is still developing, but the technical barriers are being broken down.

How are regional hubs different from local vaccine assembly?

Assembly means filling vials with vaccine concentrate made elsewhere. True manufacturing means producing the active ingredient from scratch-growing viruses, purifying proteins, or synthesizing mRNA. Assembly is faster and cheaper, but it doesn’t build long-term capacity. Manufacturing equity requires full production capability, not just packaging.

What happens if funding for these hubs dries up?

Without predictable demand and long-term financing, hubs risk becoming white elephants. That’s why the African Union’s commitment to buy 15% of its vaccines locally by 2030 is so vital. It turns charity into commerce. If governments guarantee purchases, private investors will step in. Without that, hubs may survive emergencies but collapse during normal times.

Is this initiative only about COVID-19?

No. The goal is to build infrastructure that can produce vaccines for any disease-polio, TB, malaria, Ebola, or the next unknown virus. The WHO’s 2025 TB vaccine report explicitly links manufacturing equity to future access. If we don’t fix this now, the next pandemic will repeat the same mistakes.