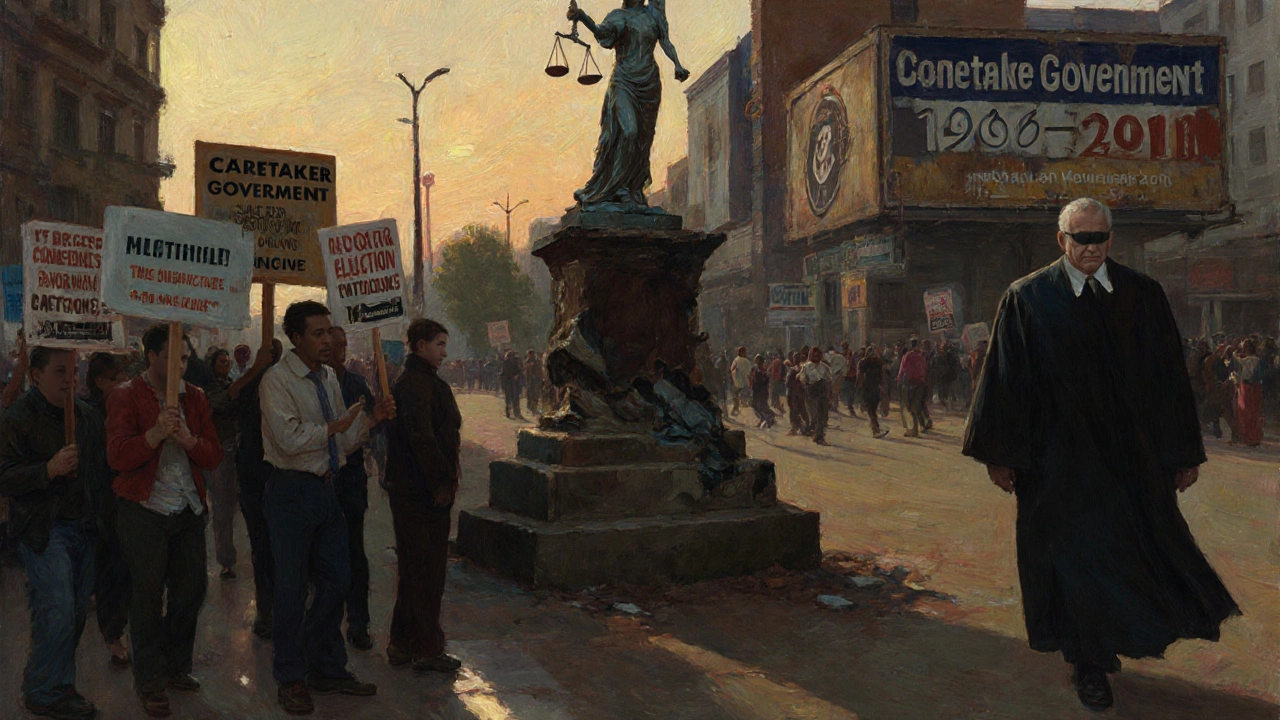

When a country holds elections, the real test isn’t just who wins-it’s whether people believe the process was fair. In Bangladesh, that question tore the country apart for decades. The caretaker government system, meant to ensure neutral elections, became a flashpoint for debates over who really controls the courts. And what happened there isn’t just a story about South Asia. It’s a warning to any democracy where judges are caught between politics and the rule of law.

What Was the Caretaker Government System?

Bangladesh introduced the caretaker government system in 1996 after years of election fraud. The idea was simple: before each national vote, an interim, non-partisan government would take over. It would run the country for 90 days, manage the election, and hand power back to whoever won. No ruling party could manipulate the process. No state resources would be used to favor one side. The caretaker government was supposed to be a neutral referee.

But here’s the catch: who chose the caretaker government? The answer was the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. That meant the head of the judiciary had the power to appoint the body meant to protect democracy. Suddenly, the courts weren’t just interpreting laws-they were running elections. And that blurred the line between judicial independence and political control.

Why Judicial Independence Matters More Than You Think

Judicial independence isn’t about judges being untouchable. It’s about them being free from pressure-whether from the president, the military, or the ruling party. In a healthy democracy, courts settle disputes between branches of government. They protect minority rights. They check abuse of power. But when judges are asked to also manage elections, they become part of the game, not the umpire.

In Bangladesh, the Chief Justice’s role in selecting caretaker governments created a dangerous precedent. If the judiciary was seen as aligned with one party, voters lost trust. In 2007, when the military-backed caretaker government took over and arrested political leaders-including future Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina and Khaleda Zia-people started asking: was this really about clean elections, or was it a power grab dressed up as reform?

That year, the caretaker government suspended civil liberties, delayed elections for two years, and jailed dozens of politicians. The Supreme Court, which had approved the move, faced accusations of complicity. The courts weren’t protecting democracy-they were enabling its suspension.

The 2011 Repeal: A Democracy’s Backlash

By 2011, public anger had grown too loud to ignore. The caretaker system was abolished by a constitutional amendment passed by the ruling party. The government argued it was outdated, undemocratic, and gave too much power to unelected officials. But the deeper truth? The system had lost legitimacy. People no longer believed the courts could be neutral.

When the Supreme Court upheld the repeal, it didn’t just change a rule-it confirmed a shift in power. The judiciary, once seen as the guardian of elections, was now seen as part of the political machine. And without the caretaker system, who would ensure fair elections? The answer was: no one, officially. The Election Commission, already underfunded and politically influenced, was left alone to handle the job.

What Happened After the System Ended?

The 2014 and 2018 elections were marred by boycotts, violence, and accusations of ballot stuffing. The main opposition party, the BNP, refused to participate in 2014, calling the vote a sham. In 2018, international observers reported widespread irregularities. Voter turnout numbers were inflated. Ballot boxes went missing. Opposition candidates were arrested on dubious charges.

Without the caretaker system, there was no institutional check on the ruling party’s power. The courts didn’t step in to stop it. Why? Because the judiciary itself had been weakened. Judges were appointed based on loyalty, not merit. Cases against government officials dragged on for years-or disappeared entirely. The Supreme Court’s rulings on election disputes became predictable: always in favor of the incumbent.

What Bangladesh learned the hard way is this: you can’t outsource democracy to a judge. If the courts aren’t trusted, no temporary government can fix that. And if the courts are politicized, they become part of the problem.

Lessons for Other Democracies

Bangladesh’s experience isn’t unique. In Pakistan, the military has used judicial rulings to sideline elected leaders. In Thailand, courts have dissolved opposition parties. Even in the United States, questions about partisan bias in judicial appointments have grown louder.

The lesson isn’t that judges should stay out of politics entirely. It’s that they shouldn’t be the ones running the game. Elections need independent commissions-not judges with extra duties. Transparency needs public oversight-not secret court decisions. Accountability needs real consequences-not delays that last years.

Strong democracies don’t rely on one person or one institution to save them. They build systems where power is shared, checked, and visible. Bangladesh tried to solve its election crisis by giving more power to the courts. It backfired. The real fix wasn’t more judicial authority-it was more institutional balance.

Can Democracy Survive Without Neutral Courts?

Democracy doesn’t die with a coup. It dies slowly, when people stop believing the rules apply to everyone equally. In Bangladesh, that belief eroded because the courts, once seen as impartial, became tools of the powerful.

Rebuilding trust takes more than new laws. It takes independent appointments, public hearings, and real consequences for corruption. It means judges are selected by a broad panel of legal experts, not the ruling party. It means election commissions have real funding, real authority, and real protection from political interference.

Bangladesh’s caretaker system was a bandage on a broken bone. It looked like a solution, but it didn’t heal the underlying rot. The real challenge isn’t finding a temporary fix for elections. It’s building institutions that can last-no matter who’s in charge.

What Comes Next for Bangladesh?

Today, Bangladesh’s Election Commission remains underfunded and politically vulnerable. Judges are still appointed based on loyalty. Protests over election fairness continue. And every vote still carries the shadow of doubt.

There’s no quick fix. But there are starting points: create a truly independent election commission with legal immunity from political pressure. Require public disclosure of all judicial appointments. Let civil society monitor vote counting. Allow international observers without restrictions.

The caretaker system is gone. But the question it raised remains: who do you trust to protect democracy when the powerful want to keep control? The answer shouldn’t be a judge. It should be a system.

Why was the caretaker government system created in Bangladesh?

The caretaker government system was created in 1996 to prevent the ruling party from manipulating elections. Before each national vote, an interim, non-partisan government-appointed by the Chief Justice-would take over for 90 days to run elections fairly. It was meant to stop vote-rigging, misuse of state resources, and intimidation of voters.

How did the judiciary gain control over elections in Bangladesh?

The Constitution gave the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court the power to appoint the head of the caretaker government. That meant the judiciary, not an elected body or independent commission, controlled who ran the election. Over time, this made the courts look like political players, not neutral referees.

Why was the caretaker system abolished in 2011?

It was abolished because it lost public trust. After the 2007 military-backed caretaker government arrested political leaders and suspended civil liberties, people saw it as a tool for authoritarian control-not fair elections. The ruling party used this loss of legitimacy to push through a constitutional amendment ending the system.

What happened to elections after the caretaker system ended?

Elections became more contested and less credible. The 2014 election was boycotted by the main opposition party. In 2018, international observers reported ballot stuffing, inflated turnout numbers, and arrests of opposition candidates. Without the caretaker system, there was no strong, neutral body to oversee the process.

Can judicial independence exist if judges run elections?

No. When judges are given executive power-like running elections-they become part of the political system. Their decisions are no longer seen as impartial. This undermines public trust in the entire judiciary. True judicial independence means interpreting laws, not making or enforcing them.

What’s the biggest lesson from Bangladesh’s experience?

You can’t fix democracy with a temporary fix. The caretaker system was a bandage, not a cure. Real change requires strong, independent institutions-like an empowered election commission, transparent judicial appointments, and legal protections for opposition parties. Democracy survives when power is shared, not concentrated.