Battery Impact Calculator

Calculate Your Battery's Impact

See the true environmental and social costs behind your electric vehicle battery

Your Battery's Impact

Equivalent to X Olympic swimming pools

Equivalent to Y tons of CO2

Child labor risk: High

Water scarcity impact: High

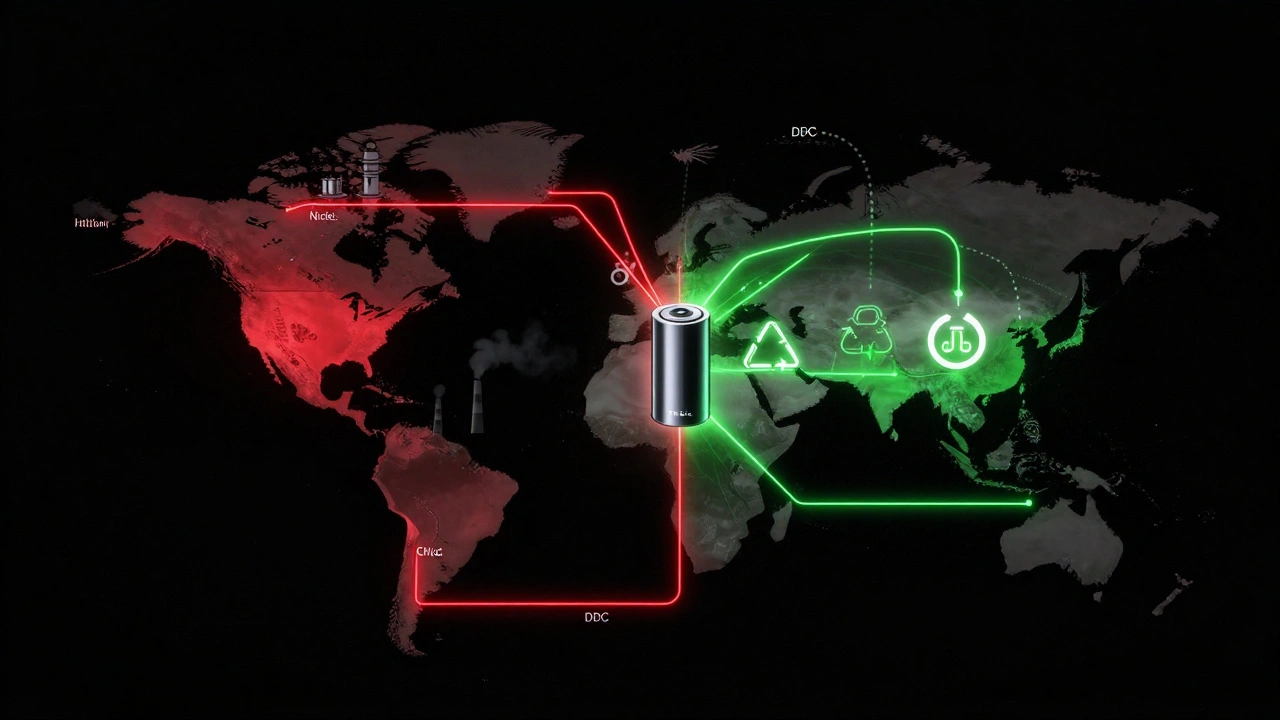

When you buy an electric car, you’re not just buying a vehicle-you’re buying a battery made of lithium, nickel, and cobalt. These aren’t ordinary metals. They’re the hidden backbone of the energy transition. But behind every green promise is a messy, high-stakes supply chain with serious environmental, social, and governance risks that most consumers never see.

Water, Waste, and Carbon: The Environmental Toll

Lithium extraction in Chile’s Atacama Desert uses 500,000 gallons of water per ton of lithium. That’s enough to fill two Olympic swimming pools. And it’s not just water-it’s the lifeblood of entire communities. The Salar de Atacama has seen its water table drop by 65% since lithium mining began. Indigenous Lickan Antay people are suing mining companies because their wells have dried up. The land is cracking. The salt flats, once vibrant ecosystems, are turning into dust bowls. Hard rock lithium mining in Australia isn’t much better. It pumps out 15,000 kg of CO2 equivalent per ton of lithium carbonate. Brine extraction is slightly cleaner at 7,500 kg CO2e per ton-but still uses nearly 2 million liters of water. There’s no clean way to get lithium out of the ground without paying a heavy environmental price. Nickel is even worse. Laterite nickel ores, which make up most of the world’s supply, generate 10 to 100 times more solid waste than copper mining. For every ton of nickel, you get 50 to 100 tons of waste rock and tailings. These piles sit in tropical regions like Indonesia and the Philippines, where heavy rains turn them into toxic sludge. The World Mine Tailings Failures database predicts 13 catastrophic failures between 2025 and 2029. One collapse could poison rivers, kill fish, and displace entire villages. And then there’s carbon. Nickel sulfate production for EV batteries emits 18 to 25 tons of CO2e per ton of nickel. That’s 30% higher than the average for base metals. Cobalt refining? It’s worse-28 tons of CO2e per ton. China controls 80% of cobalt refining, and most of that refining runs on coal-fired power. So when you charge your EV, you might be using electricity generated from coal halfway around the world.Cobalt’s Human Cost

If lithium is an environmental crisis, cobalt is a human rights emergency. The Democratic Republic of Congo supplies 70% of the world’s cobalt. And in the DRC, about 15 to 30% of that cobalt comes from small, informal mines-often dug by hand with no safety gear, no ventilation, no pay. Amnesty International reported 40,000 children working in these mines as of 2025. Kids as young as seven climb down narrow shafts, carrying 50-pound sacks of ore on their backs. They’re exposed to toxic dust. Many get sick. Some die. These aren’t statistics-they’re real children, and they’re working because their families have no other choice. Even when companies claim to use “conflict-free” cobalt, the traceability is broken. A 2026 survey of 800 chief procurement officers found that 68% couldn’t verify ESG compliance beyond their first-tier suppliers. That means if a refinery says it’s buying from a “responsible” mine, you have no idea if that mine is connected to a child labor operation three steps down the chain. And it’s not just about children. Workers in artisanal mines earn less than $2 a day. There’s no healthcare. No union. No safety training. The World Economic Forum says these human rights risks are now material financial liabilities. Major battery makers like CATL and LG Energy Solution now require third-party verified cobalt sourcing-because investors won’t fund companies linked to abuse.The Supply Chain Is Broken

The problem isn’t just extraction-it’s control. China owns 60% of lithium refining, 35% of nickel refining, and 80% of cobalt refining. That means even if you mine lithium in Australia or nickel in Canada, you still have to ship it to China to turn it into battery-grade material. And if China decides to restrict exports-or if a ship gets stuck in the Strait of Malacca-you’re stuck. This isn’t hypothetical. In 2022, lithium prices spiked 500% in six months because one mine in Australia had a technical issue. Automakers scrambled. Battery factories paused production. The whole system cracked under pressure. The “chicken-and-egg” problem is real. Miners won’t build new mines unless they have long-term buyers. But automakers won’t sign contracts unless they’re sure the supply is ethical and reliable. So nothing moves. The lead time to develop a new mine is 10 to 15 years. Battery factories can be built in 2. That mismatch is a ticking time bomb.

Regulations Are Catching Up

Governments are finally stepping in. The EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) started full enforcement on January 1, 2026. Now, every ton of imported nickel, lithium, or cobalt is taxed based on its carbon footprint. If your cobalt was refined in a coal-powered plant in China, you pay more. If your lithium came from a brine operation that recycled 85% of its water, you pay less. The EU’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) also kicked in this year. It forces 49,000 companies to report their ESG risks in detail-with limited third-party assurance. That means if you’re a Tesla, Ford, or Hyundai supplier, you can’t just say “we source responsibly.” You need to prove it. With data. With audits. With blockchain traceability. The U.S. Inflation Reduction Act is pushing the same direction. By 2027, at least half the critical minerals in every EV battery sold in the U.S. must come from North America or a free-trade partner. That’s forcing automakers to look at new sources: clay-based lithium in Nevada, nickel in Canada, and cobalt from recycled batteries in Ohio. And it’s not just governments. The International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM) now requires members to deliver measurable biodiversity improvements by 2028. Over 730 companies-including 179 financial institutions managing $22 trillion in assets-have signed on. They’re pulling funding from mines that don’t meet the new standards.What’s Being Done-and What’s Working

Some companies are stepping up. Tesla now uses cobalt-free LFP batteries in its standard-range models. That cuts demand by 30%. Ford and Rivian are investing in direct lithium extraction (DLE) tech that uses 90% less water than traditional brine mining. In Nevada, a startup called Lilac Solutions is testing a new method that pulls lithium from clay using ion exchange-no evaporation ponds, no desert aquifers drained. Recycling is another lifeline. Today, less than 5% of lithium-ion batteries are recycled. But new facilities in the U.S. and Europe can now recover 95% of cobalt, nickel, and lithium from spent batteries. By 2030, recycled materials could supply up to 25% of global demand. That’s not enough-but it’s a start. Water recycling systems cost $45 to $60 million upfront, but they slash freshwater use by 85%. Companies like Albemarle and SQM are installing them in Chile and Argentina. The ROI isn’t immediate, but the risk of shutdowns from water protests? That’s a bigger cost. Full traceability is still expensive. Mapping a supply chain from mine to battery costs about $2.1 million per company and takes 6 to 9 months. But for automakers under EU CSRD, it’s non-negotiable. One major supplier told us they lost a $400 million contract because they couldn’t prove their cobalt wasn’t linked to child labor-even though they had no direct involvement.

The Road Ahead

The energy transition can’t stop. But it can’t keep moving forward on broken foundations. Lithium, nickel, and cobalt are essential-but they’re not magic. They’re minerals. And mining them has consequences. The companies that survive the next decade won’t be the ones with the cheapest batteries. They’ll be the ones with the most transparent, responsible, and resilient supply chains. That means investing in recycling. Supporting new mining tech. Demanding traceability. Paying more for ethical sourcing. The consumer’s role? It’s not about boycotting EVs. It’s about asking: Where did this battery come from? If you care about climate change, you have to care about the people and places that make your EV possible. Otherwise, you’re just trading one kind of damage for another.What You Can Do

- Look for EVs that use recycled or ethically sourced batteries. Some brands now label them. - Support policies that fund recycling infrastructure and domestic mining with strict ESG rules. - Ask your employer, school, or city to require ESG-compliant suppliers for fleet vehicles. - Don’t assume “green” means clean. Demand proof. The energy transition isn’t a finish line. It’s a journey-and we’re still at the starting gate. Getting it right means facing hard truths. Not just about technology, but about justice, water, and who pays the price for progress.Why is lithium extraction so water-intensive?

Lithium from brine deposits, which account for about 60% of global supply, requires pumping saltwater from underground aquifers into giant evaporation ponds. The sun evaporates the water over 12 to 18 months, leaving behind lithium-rich crystals. This process uses about 500,000 gallons of water per ton of lithium. In places like Chile’s Atacama Desert, where water is already scarce, this drains local supplies and harms ecosystems and indigenous communities.

Is cobalt mining always linked to child labor?

No, not always-but the risk is extremely high in the Democratic Republic of Congo, which supplies 70% of the world’s cobalt. About 15 to 30% of cobalt from the DRC comes from artisanal mines where child labor is documented. Large mining companies and refined cobalt from Western Australia or Canada have no child labor. The problem is traceability: many supply chains mix artisanal and industrial cobalt, making it hard to know the source. Since 2025, major battery makers require verified, audited cobalt sources to avoid this risk.

Can recycling solve the cobalt and lithium supply problem?

Recycling won’t solve it alone, but it’s a critical part of the solution. Today, less than 5% of lithium-ion batteries are recycled. New facilities in the U.S. and Europe can recover up to 95% of cobalt, nickel, and lithium from spent batteries. By 2030, recycled materials could meet 20 to 25% of global demand. That reduces pressure on new mines and cuts carbon emissions by up to 50% compared to virgin mining. The bottleneck is collection infrastructure-not technology.

Why does China control so much of the refining process?

China invested heavily in refining technology and infrastructure over the past 20 years. They built large-scale, low-cost plants and secured long-term contracts with mining countries. Refining lithium, nickel, and cobalt into battery-grade materials is complex and capital-intensive. Most countries outside China never built this capacity. Now, even if you mine lithium in Australia or cobalt in Canada, you still need to send it to China to process it. This creates a major supply chain vulnerability.

Are there alternatives to lithium, nickel, and cobalt?

Yes, but not yet at scale. Lithium iron phosphate (LFP) batteries don’t use nickel or cobalt and are already common in entry-level EVs. Solid-state batteries, still in development, may reduce or eliminate cobalt. Sodium-ion batteries are emerging as a low-cost, cobalt-free option for grid storage. But for high-performance EVs, lithium, nickel, and cobalt are still the most efficient. The goal isn’t to eliminate them-it’s to mine and refine them responsibly.