When the United Nations sends peacekeepers to a war zone, people expect them to stop the fighting. But in places like Mali, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, or South Sudan, peacekeepers often arrive to find their mission was never meant to end the war-only to manage it. The gap between what the world expects and what UN peacekeeping can actually deliver is growing wider. And it’s not because the soldiers aren’t brave. It’s because the rules they operate under, and the tools they’re given, were never built for the wars of today.

Peacekeeping Was Never Meant for Full-Scale War

The UN’s first peacekeeping missions in the 1950s were simple: monitor a ceasefire between two armies that had agreed to stop shooting. Think Egypt and Israel after the Suez Crisis. The peacekeepers didn’t carry heavy weapons. They didn’t hunt down rebels. They just watched, reported, and stayed neutral. That model worked when conflicts were between states with clear borders and command structures.

Today, most conflicts are internal. Armed groups shift identities overnight. Militias control entire towns. Governments are weak or complicit. In Mali, peacekeepers face jihadists who don’t wear uniforms, don’t follow rules, and don’t care about UN resolutions. In the DRC, over 120 armed groups operate in the east. The UN’s mandate doesn’t let them go after all of them-only the ones named in the resolution. And even then, they need permission from the host government, which often has ties to the very groups they’re supposed to stop.

Mandates Are Written by Politicians, Not Soldiers

The UN Security Council writes peacekeeping mandates. That means decisions about what peacekeepers can and can’t do are made in New York, often by countries that haven’t seen a battlefield in decades. A mandate might say: "Protect civilians under imminent threat of physical violence." Sounds clear. But what counts as "imminent"? If a village is surrounded by fighters who’ve just killed 10 people nearby, is that imminent? What if the attackers are 15 kilometers away? There’s no standard. Commanders on the ground make split-second calls with no legal backup.

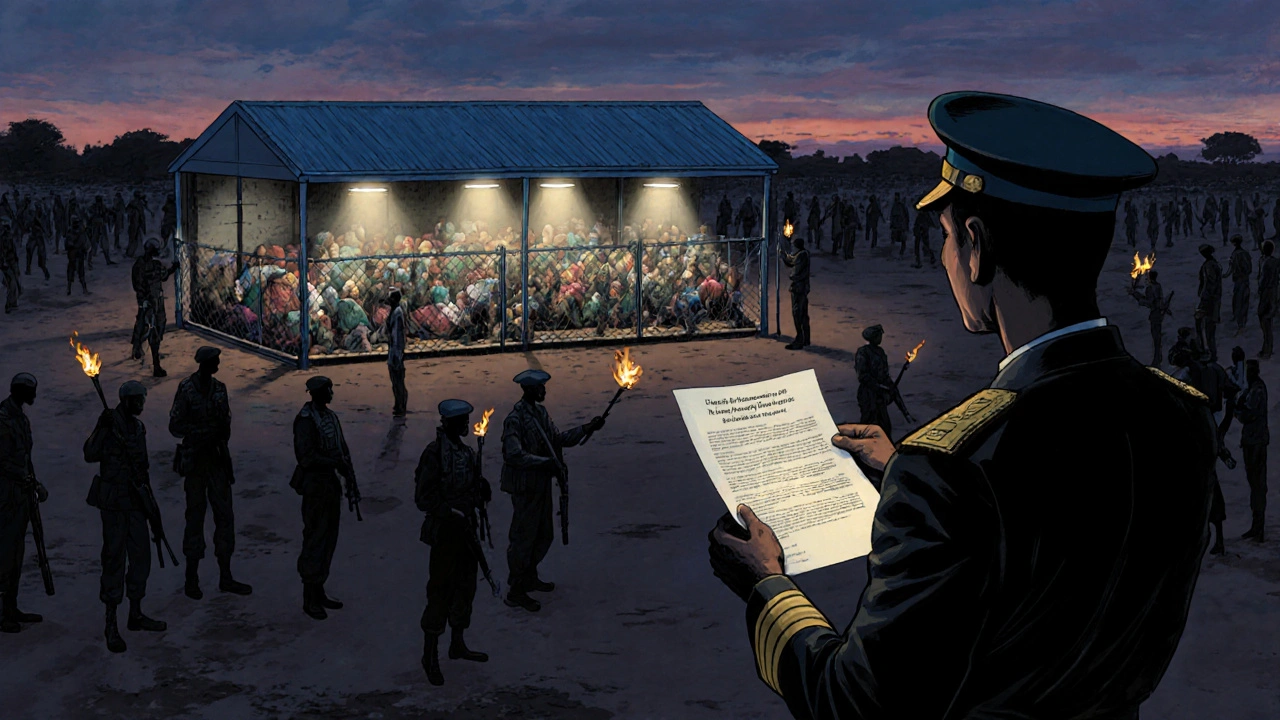

In 2014, in South Sudan, UN peacekeepers sheltered 8,000 civilians inside a base. When armed groups surrounded the base and started shooting, the peacekeepers couldn’t leave to rescue people outside. Their mandate didn’t authorize offensive action. They could protect those inside, but not go out. Over 100 people died in the surrounding area. The world called it a failure. The UN called it a mandate limitation.

Resources Don’t Match the Mission

UN peacekeeping is the world’s largest military operation without its own army. It borrows troops from 120 countries. Some send well-trained units. Others send under-equipped soldiers with minimal training. In 2023, the average peacekeeper came from a country where the military budget was less than $50 per person per year. Meanwhile, the UN’s annual peacekeeping budget was $6.1 billion.

That money doesn’t go far. About 60% of it pays for troop reimbursements. Another 20% goes to logistics-fuel, food, helicopters. Only 10% goes to intelligence, surveillance, or modern equipment. Many peacekeeping bases still use radios from the 1990s. Drones? Rare. Cyber defense? Nonexistent. When a convoy gets ambushed in the Central African Republic, the response often takes hours because there’s no real-time tracking or rapid reaction force nearby.

And the troop contributors? They’re not always motivated by global peace. Some send troops because the UN pays $1,400 per soldier per month-more than their own army pays. Others use peacekeeping as a way to train soldiers without risking domestic political fallout. The result? Missions are staffed, but not always effectively.

The Host Country Problem

Peacekeepers can’t operate without the host government’s permission. That sounds fair. But in places like Sudan or the DRC, the government is part of the problem. They block access to conflict zones. They deny visas to UN investigators. They restrict movement so their allies can keep looting. In 2022, the DRC government refused to let UN observers enter a region where mass graves were reported. The UN couldn’t act. No mandate, no access, no power.

Even when governments agree to peacekeeping, they often demand restrictions. In Lebanon, the UN mission (UNIFIL) can’t enter certain areas controlled by Hezbollah. In Cyprus, peacekeepers can’t cross the Green Line without permission from both sides. These aren’t neutral zones-they’re political traps. The UN’s neutrality becomes a cage.

What Happens When Peacekeepers Fail?

When a peacekeeping mission collapses, the consequences aren’t just local. They ripple through global security. In 2021, after the UN pulled out of northern Mali due to attacks and political pressure, the region became a haven for terrorist groups linked to ISIS and Al-Qaeda. Within a year, attacks spread to Burkina Faso and Niger. European countries saw a spike in refugee flows. The cost? Billions in new military aid, intelligence ops, and border security.

And the human cost? Children recruited as soldiers. Women targeted in mass sexual violence. Entire villages abandoned. The UN can’t fix these problems with checkpoints and patrols. But it’s the only international body trying.

Real Fixes, Not Just More Troops

More soldiers won’t solve this. Neither will more resolutions. What’s needed is a new approach:

- Flexible mandates: Let peacekeepers act when civilians are at risk, not just when a resolution lists specific groups. A rule like "protect civilians from any armed threat"-not just those named in a document written in New York.

- Real funding for intelligence: Invest in satellite imagery, drone surveillance, and local informant networks. Without knowing where the threats are, peacekeepers are just waiting to be attacked.

- Regional partnerships: Work with African Union forces, ECOWAS, or SADC. These groups understand local dynamics better than the UN. In Somalia, AU troops have been more effective than UN peacekeepers for years. Let them lead-with UN support.

- Accountability for host governments: If a country blocks access to war crimes, cut funding. If they obstruct peacekeepers, impose sanctions. The UN has the power. It just refuses to use it.

There’s also a moral question: Should the UN even be in places where no peace exists to keep? In some cases, the answer might be no. Sending peacekeepers into a war zone without the means or mandate to end it doesn’t bring peace. It just delays the inevitable-and gives the world a false sense of doing something.

What Comes Next?

UN peacekeeping isn’t broken. It’s outdated. The world still relies on it because there’s no better alternative. But clinging to 1950s rules in 2025 is dangerous. If the UN doesn’t adapt, it will keep sending soldiers into situations they can’t win. And every time that happens, another child dies because the world thought someone else was watching.

The solution isn’t more money. It’s more honesty. Admit when a mission can’t succeed. Redesign mandates to match reality. Give peacekeepers the tools to protect, not just observe. And stop pretending that watching a war is the same as stopping it.

Why can’t UN peacekeepers just use force to stop fighting?

UN peacekeepers are not a military force-they’re observers with limited rules of engagement. They can only use force in self-defense or to protect civilians under imminent threat. They can’t launch offensives, hunt down armed groups, or take control of territory. Those actions require a Chapter VII mandate, which the Security Council rarely approves because it risks escalating conflict or violating sovereignty.

Which countries contribute the most troops to UN peacekeeping?

As of 2025, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Rwanda, and Ethiopia are the top five troop contributors. Together, they provide over 40% of all UN peacekeepers. These countries often send large numbers of soldiers because the UN pays significantly more than their national military salaries-around $1,400 per soldier per month. This creates a financial incentive, but also raises concerns about training quality and mission commitment.

How much does UN peacekeeping cost each year?

In 2025, the UN peacekeeping budget was $6.1 billion. About 60% of that goes to reimburse troop-contributing countries for personnel, equipment, and logistics. Another 20% covers operational costs like fuel, food, and transport. Only 10% is spent on modern tools like drones, intelligence systems, or cyber defenses. The rest covers administration and support services.

Why don’t major powers like the US or UK send more troops?

The United States and United Kingdom provide financial support but send very few troops. The US contributes about 27% of the budget but has fewer than 100 personnel on the ground. This is partly due to domestic political resistance to foreign deployments, especially in unstable regions. There’s also a preference for using national forces in direct combat roles rather than peacekeeping. The UK focuses on specialized units like engineers or medical teams, not infantry patrols.

Are UN peacekeeping missions more successful now than in the past?

Success rates have dropped. In the 1990s, about 60% of missions achieved their primary goal. Today, that number is below 30%. The shift is due to changing conflict types: more internal wars, more non-state actors, and weaker host governments. Missions in Mali, the DRC, and South Sudan have seen little progress despite decades of presence. The UN’s own reports admit that mandates are often unrealistic and resources insufficient.

Can peacekeeping missions be replaced by something better?

No single alternative exists yet. Regional forces like the African Union have proven more effective in some areas, but they lack funding and coordination. Private security firms are too controversial. National armies risk being seen as occupiers. The UN remains the only globally accepted framework-even if flawed. The real question isn’t replacement, but reform: Can the UN become faster, smarter, and more willing to act?