Trade Bloc Tariff Impact Calculator

Estimated Trade Impact

Trade is no longer global-it’s divided.

Five years ago, if you made a product in China and sold it in the U.S., you were just doing business. Today, you’re picking a side. The world isn’t just trading more-it’s splitting apart. Three major powers-the United States, the European Union, and China-are building walls around their economies, not with concrete, but with tariffs, export controls, and supply chain rules. And businesses are caught in the middle.

China’s trade surplus hit $1.2 trillion in 2025, its highest ever. Meanwhile, the U.S. cut its trade deficit despite slapping tariffs on nearly everything from steel to smartphones. The EU? It’s caught in between, importing far more from China than it exports. By late 2025, China’s trade surplus with Europe surpassed its surplus with the U.S. for the first time. That’s not just an economic shift-it’s a geopolitical earthquake.

The U.S. strategy: Tariffs, exemptions, and selective decoupling

Since January 20, 2026, the U.S. has doubled down on its "America First" trade policy. Tariffs on Chinese goods rose to 91% at their peak, then dropped to 30% after talks in Geneva. But the real number? The average tariff on Chinese imports is still 37.3%. That’s more than double the U.S. rate for all other countries.

Here’s the twist: companies like Apple, Walmart, and Target got exemptions. Semiconductors, smartphones, and medical devices? Still flowing in with little to no extra cost. Why? Because cutting those off would hurt American consumers and businesses more than it hurts China. The U.S. isn’t trying to cut China out completely-it’s trying to force a reshuffle.

Imports from China fell 25% between January and September 2025. But imports from the EU rose nearly 10% in the same period. The U.S. isn’t just targeting China-it’s pulling supply chains toward Europe, Mexico, and Vietnam. The goal? Reduce dependence, not eliminate it.

And yet, experts say the pain is one-sided. A 2026 report from Epoch Investment Partners found that China can absorb trade pressure longer than the U.S. can. Why? China controls 90% of the world’s rare earth minerals-critical for electric vehicles, wind turbines, and defense tech. When the U.S. threatened to cut off tech exports, China threatened to cut off the minerals. The U.S. backed down. That’s not negotiation. That’s leverage.

The EU’s dilemma: Caught between two giants

The European Union has one of the world’s largest economies. But it doesn’t have the leverage. In 2024, the EU imported €732 billion worth of goods from China and exported only €426 billion. That’s a €305.8 billion deficit-the largest ever. And it’s getting worse.

China’s steel exports surged 6.6% in December 2025, even as the EU and U.S. tried to block them with new tariffs. German automakers are being hit hardest. China produced over 15 million electric vehicles in 2026-up 33% from the year before. Nearly all of them are exported. Germany, which used to dominate EV production, now faces Chinese models undercutting them by 20-30% in price.

Meanwhile, the EU is trying to play both sides. It’s enforcing its Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), taxing imports based on their carbon footprint. It’s also making Import Control System 2 (ICS2) mandatory for UK traders, tightening customs checks. But these rules don’t hurt China-they hurt European businesses trying to compete.

And now the U.S. is turning its attention to Europe. In early 2026, the Trump administration demanded the EU roll back its Digital Services Act and AI regulations, calling them "non-tariff barriers." The message? Follow our rules, or face consequences. Belgium, with its export-heavy economy, is already bracing for a shock. Allianz Trade warned that Europe could become the "main target" of U.S. trade policy if tensions rise again.

China’s countermove: Diversify alliances, control resources

China isn’t just defending its exports-it’s building new trade networks. In January 2026, President Xi Jinping called Canada a "new strategic partner." That’s not just diplomacy. It’s supply chain realignment. Canada supplies lithium, nickel, and rare earths. China is locking in those resources before the U.S. can.

China’s exports to the U.S. dropped from 14.7% of its total exports in 2024 to just 11.1% in 2025. Where did they go? Southeast Asia, Latin America, Africa. China is now the top trading partner for over 120 countries. It’s not replacing the U.S. market-it’s bypassing it.

And here’s the quiet power play: China doesn’t need to export as much to the U.S. to win. It just needs to make sure the U.S. can’t live without what it still buys. Rare earths. Solar panels. Batteries. Electric motors. China produces them all. The U.S. can’t. That’s why, despite 100% tariffs, Chinese tech still flows into American warehouses-because there’s no alternative.

What’s really changing: Selective decoupling, not total separation

Forget the idea of a full economic divorce between the U.S. and China. That’s not happening. Instead, we’re seeing selective decoupling. High-tech goods? Restricted. Low-margin goods? Still flowing. Critical minerals? Controlled. Consumer electronics? Still exempt.

Trade between the U.S. and China still hit $688.3 billion in 2024-275 times what it was in 1979. That’s not a collapsing relationship. That’s a restructured one.

Five phone calls between Xi and Trump, and five high-level meetings, led to a fragile truce: the U.S. suspended 24% tariffs on Chinese goods for a year. In return, China paused rare earth export bans. It wasn’t peace. It was a pause. Both sides know the next round is coming.

Global trade growth in 2026 is projected at just 2.6%. The World Bank says it’s the weakest decade since the 1960s. But that’s not because trade is dying. It’s because it’s being redirected. Companies are now choosing which bloc to align with. And that choice affects everything-from sourcing materials to where you build factories.

The new rules of cross-border commerce

If you’re running a business today, you can’t just think about cost and speed. You have to ask: Which side am I on?

- If you rely on Chinese components, are you exposed to rare earth export controls?

- If you sell in Europe, will your carbon footprint trigger CBAM taxes?

- If you source from Vietnam or Mexico, can you prove your supply chain isn’t tied to China?

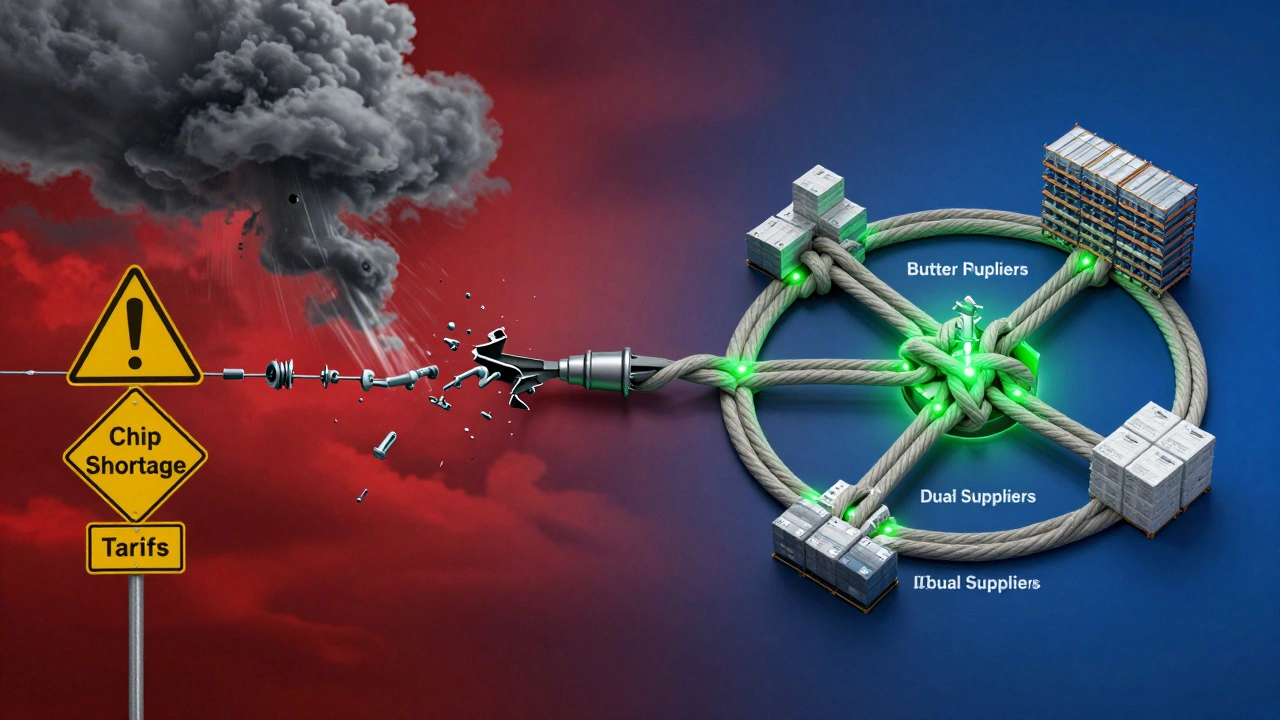

Companies that succeed will be the ones who build flexible, multi-regional supply chains. Those that try to pick one side and stick to it? They’ll get squeezed.

And governments? They’re not just setting tariffs. They’re rewriting the rules of global trade. The old system-open markets, WTO rules, free flow of goods-is fading. What’s replacing it? Three competing spheres, each with its own standards, its own allies, and its own punishments.

There’s no going back. The future of commerce isn’t about who produces the cheapest goods. It’s about who controls the infrastructure, the resources, and the alliances that make production possible.

What’s next? The next 12 months will decide the shape of trade for a decade

Look for these signals in 2026 and 2027:

- Will the U.S. expand its 25% tariff on countries trading with Iran to include China-linked firms?

- Will the EU impose carbon taxes on Chinese EVs, triggering retaliatory tariffs?

- Will Canada’s new partnership with China lead to a North American supply chain bloc?

- Will U.S. tech firms lobby harder for more exemptions, or push for full decoupling?

One thing is clear: trade is no longer about efficiency. It’s about security. And security doesn’t care about low prices. It cares about control.

Businesses that ignore this shift won’t just lose market share. They’ll lose access to markets entirely.

Are regional trade blocs replacing global trade?

Not replacing-restructuring. Global trade still exists, but it’s now divided into three main zones: the U.S.-aligned bloc, the EU-aligned bloc, and the China-aligned bloc. Companies can’t operate the same way across all three. They must choose which rules to follow, which suppliers to trust, and which markets to prioritize.

Why is China’s trade surplus with Europe bigger than with the U.S. now?

Because Europe imports far more from China than it exports. In 2024-2025, China’s surplus with Europe hit $310 billion, surpassing its $302 billion surplus with the U.S. Europe relies on Chinese manufacturing for electronics, machinery, and consumer goods. It hasn’t built enough domestic alternatives, and its own industries are struggling to compete on price and scale.

Can the U.S. really decouple from China economically?

Not fully-and it doesn’t want to. The U.S. still needs Chinese-made solar panels, batteries, and rare earth processing. What it wants is to reduce dependency, not eliminate it. The goal is to have backup suppliers in India, Vietnam, or Mexico while keeping critical Chinese supply chains on a short leash through tariffs and tech bans.

How are tariffs affecting everyday products?

Tariffs on Chinese goods have pushed prices up on things like electronics, furniture, and toys-but not as much as you’d think. Companies like Apple and Walmart got exemptions for smartphones and home goods. The real impact is on smaller businesses that can’t afford legal teams to apply for waivers. For them, tariffs mean higher costs, slower shipments, and fewer options.

Is the EU losing its economic sovereignty?

It’s being pulled in two directions. The U.S. wants Europe to align with its tech and trade rules. China offers cheaper goods and investment. The EU’s own rules-like carbon taxes and digital regulations-are being used as weapons by both sides. Without a unified strategy, Europe risks becoming a pawn, not a player, in global trade.